Brief History of UNB: Difference between revisions

Markmcumber (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Markmcumber (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

= College of New Brunswick (1800 - 1828) = | = College of New Brunswick (1800 - 1828) = | ||

[[File:College of New Brunswick.jpg|thumb|right|320x255px | [[File:College of New Brunswick.jpg|thumb|right|320x255px]] Although the draft charter had been drawn up in 1785, and although the Academy was functioning shortly afterwards, at first in a cottage on what is now University Avenue, and by 1793 in its own building, the actual granting of the charter was delayed, "because of the opposition of the Bishop of Nova Scotia, who looked upon the college in Fredericton as a rival of King's College which was at the same time being established in Windsor, Nova Scotia." On 12 February 1800, the Academy was transformed into the College of New Brunswick by provincial charter. The Reverend James Bisset was the first principal. The first council of the College consisted of Chief Justice Ludlow, a former judge of the Supreme Court of New York; Jonathan Odell, the Loyalist poet of the American Revolution; Edward Winslow, an illustrious founder of the Province; and Colonel Isaac Allen of the New Jersey Volunteers. Andrew Phair, one of the early teachers, served under Benedict Arnold during the Revolutionary War. The little College, presided over after 1811 by the [[Presidents|Reverend James Somerville]], was set in a scene of pastoral beauty. In the words of a visitor in 1804, Fredericton was a pretty thing, "a village scattered on a delightful common on the richest sheep pasture I ever saw, the flocks grazing up to our door. There are altogether about a hundred and twenty houses, some very pretty, all comfortable looking, and almost everyone has a garden." | ||

[[#top|Top]] | [[#top|Top]] | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

Population and prosperity increased rapidly. By 1823 the Province had grown sufficiently in economic and social strength to warrant the expansion of the old College; and largely as the result of the vigorous policy of Sir Howard Douglas, the older institution surrendered its charter, and King's College was established by Royal Charter. Opening the [[Old Arts Building|College]] on its new site on the hill, New Year's Day, 1829, Sir Howard sounded the note that has inspired more recent generations: "Firm may this institution ever stand and flourish—firm in the liberal constitution and Royal foundation on which I have this day instituted it—enlarging and extending its material form and all its capacity to do good, to meet the increasing demands of a rising, prosperous and intellectual people; and may it soon acquire and ever maintain a high and distinguished reputation as a place Of general learning and useful knowledge." | Population and prosperity increased rapidly. By 1823 the Province had grown sufficiently in economic and social strength to warrant the expansion of the old College; and largely as the result of the vigorous policy of Sir Howard Douglas, the older institution surrendered its charter, and King's College was established by Royal Charter. Opening the [[Old Arts Building|College]] on its new site on the hill, New Year's Day, 1829, Sir Howard sounded the note that has inspired more recent generations: "Firm may this institution ever stand and flourish—firm in the liberal constitution and Royal foundation on which I have this day instituted it—enlarging and extending its material form and all its capacity to do good, to meet the increasing demands of a rising, prosperous and intellectual people; and may it soon acquire and ever maintain a high and distinguished reputation as a place Of general learning and useful knowledge." | ||

Founded at a time[[File:King's college.jpg|thumb|left|372x143px|King's | Founded at a time[[File:King's college.jpg|thumb|left|372x143px|An idealized drawing of King's College, [ca. 1828]. UA PC 9; no. 2 (1). Artist: Rev. Abraham Wood.]] when New Brunswick was governed by the aristocratic ideals of the Family Compact, it was natural that the College should have reflected a Tory and Anglican bias. It was, Sir Howard had said, to act as a bulwark against the levelling influences of the neighbouring republic that were so abhorred by the governing class of that day. Indeed the intellectual tone of the College was for some time dominated by that point of view; and it gave rise to the bitter sectarian quarrels of the mid-century that marked one aspect of the struggle of the people of the Province for democratic self-government. The demand for religious liberty led to the abolition of religious tests in 1846. Classics, moral philosophy, logic, Hebrew, divinity and metaphysics were prominent subjects in the curriculum. Instruction became broader and increasingly "practical", as time went on, especially under the able leadership of [[Presidents|William Brydone Jack]] and James Robb, who brought to New Brunswick the best scientific traditions of the great Scottish universities. While attending with great success to his professional duties, Dr. Robb did much to bring the benefits of the College to the people of the Province. He was the first scientific botanist in New Brunswick. He was the first president and the most active spirit in the Fredericton Atheneum, a society for the promotion of literary and scientific research. He commenced to write a history of the Province but died before it was completed. He founded the University Museum, and, throughout the course of his tireless life, contributed materially to the progress of agriculture and the exploration of the mineral resources of New Brunswick. His colleague, Joseph Marshall, Baron d'Avray, at one time a supporter of the Bourbon monarchy of France, founder of New Brunswick's first Normal School for the training of teachers, taught modern languages for twenty-three years, from 1848 to 1871, competently and with a courtly grace. | ||

[[#top|Top]] | [[#top|Top]] | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

= University of New Brunswick (1859 - Present) = | = University of New Brunswick (1859 - Present) = | ||

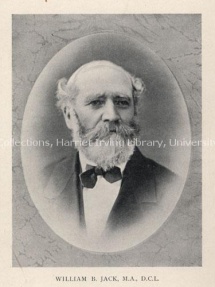

New Brunswick's change in status, from a crown colony to a province enjoying internal self-government, also had an important repercussion in the field of education. [[Presidents|Edwin Jacob]], who had served as principal for thirty years, retired in 1859, and King's College was transformed into the University of New Brunswick. Henceforth education was to be on a broader democratic basis, appealing to all creeds and classes. Under the presidency of [[Presidents|William Brydone Jack]] the University made rapid strides. Professor Montgomery-Campbell gave the students the benefit of his fine classical training, and Loring Woart Bailey, fresh from Harvard, took the chair of Chemistry and the Natural Sciences, bringing to the University the spirit that he had caught from his famous master, Louis Agassiz. For forty-six years, until his retirement in 1906, Dr. Bailey contributed greatly to the reputation of the University as a centre of scientific research.[[File:William brydone jack.jpg|thumb|right|215x371px|William | New Brunswick's change in status, from a crown colony to a province enjoying internal self-government, also had an important repercussion in the field of education. [[Presidents|Edwin Jacob]], who had served as principal for thirty years, retired in 1859, and King's College was transformed into the University of New Brunswick. Henceforth education was to be on a broader democratic basis, appealing to all creeds and classes. Under the presidency of [[Presidents|William Brydone Jack]] the University made rapid strides. Professor Montgomery-Campbell gave the students the benefit of his fine classical training, and Loring Woart Bailey, fresh from Harvard, took the chair of Chemistry and the Natural Sciences, bringing to the University the spirit that he had caught from his famous master, Louis Agassiz. For forty-six years, until his retirement in 1906, Dr. Bailey contributed greatly to the reputation of the University as a centre of scientific research.[[File:William brydone jack.jpg|thumb|right|215x371px|UNB President William Brydone Jack, 1878. MG L 32; Series 6; File 1, Box 4; Item 24.]] | ||

[[Presidents|Dr. Brydone Jack]] looked forward to the extension of the curriculum to include navigation, law, medicine, engineering and agriculture. The need for instruction in navigation belongs to that vanished era when New Brunswick was a great shipbuilding and seafaring Province; but its proposed inclusion in the curriculum was evidence of the earnest attempt to make the University serve the needs of the people. [[Presidents|Brydone Jack]]'s aims have long since been realized to the extent that instruction in law, forestry and engineering have for years been given at the University. But progress was slow in the years immediately following Confederation, for at that time financial aid was insufficient to carry out the ideas of the President. Nevertheless, so keen was the intellectual life of the University, along certain lines, that it achieved a reputation second only to that of the University of Toronto. It became the nucleus of a provincial culture, a fact that is attested to by the literary, scientific and political achievements of the graduates of those years—Sir George Parkin, whose fame as an a educationist was as wide as the British Commonwealth of Nations; Sir George Foster, one of the greatest of Canadian statesmen; [[http://www.lib.unb.ca/225/blisscarman.html Bliss Carman]] and [[http://www.lib.unb.ca/225/charlesgdroberts.html%7CSir Charles G.D. Roberts]], both famous poets; William Francis Ganong, distinguished scientist and historian of his native Province; and many others. | [[Presidents|Dr. Brydone Jack]] looked forward to the extension of the curriculum to include navigation, law, medicine, engineering and agriculture. The need for instruction in navigation belongs to that vanished era when New Brunswick was a great shipbuilding and seafaring Province; but its proposed inclusion in the curriculum was evidence of the earnest attempt to make the University serve the needs of the people. [[Presidents|Brydone Jack]]'s aims have long since been realized to the extent that instruction in law, forestry and engineering have for years been given at the University. But progress was slow in the years immediately following Confederation, for at that time financial aid was insufficient to carry out the ideas of the President. Nevertheless, so keen was the intellectual life of the University, along certain lines, that it achieved a reputation second only to that of the University of Toronto. It became the nucleus of a provincial culture, a fact that is attested to by the literary, scientific and political achievements of the graduates of those years—Sir George Parkin, whose fame as an a educationist was as wide as the British Commonwealth of Nations; Sir George Foster, one of the greatest of Canadian statesmen; [[http://www.lib.unb.ca/225/blisscarman.html Bliss Carman]] and [[http://www.lib.unb.ca/225/charlesgdroberts.html%7CSir Charles G.D. Roberts]], both famous poets; William Francis Ganong, distinguished scientist and historian of his native Province; and many others. | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

It remained, however, for the promise of the nineteenth to be fulfilled in the twentieth century. During the presidency of [[Presidents|Dr. Cecil Charles Jones]], from 1906-40, and his successors, [[Presidents|Dr. Norman MacKenzie]] (1940-44), [[Presidents|Dr. Milton F. Gregg]], V.C. (1944-47), [[Presidents|Dr. Albert W. Trueman]] (1948-53), [[Presidents|Colin B. Mackay ]](1953-69), [[Presidents|Dr. James O. Dineen]] (1970-72), and [[Presidents|Dr. John M. Anderson]] (1973-79), the University forged steadily ahead. | It remained, however, for the promise of the nineteenth to be fulfilled in the twentieth century. During the presidency of [[Presidents|Dr. Cecil Charles Jones]], from 1906-40, and his successors, [[Presidents|Dr. Norman MacKenzie]] (1940-44), [[Presidents|Dr. Milton F. Gregg]], V.C. (1944-47), [[Presidents|Dr. Albert W. Trueman]] (1948-53), [[Presidents|Colin B. Mackay ]](1953-69), [[Presidents|Dr. James O. Dineen]] (1970-72), and [[Presidents|Dr. John M. Anderson]] (1973-79), the University forged steadily ahead. | ||

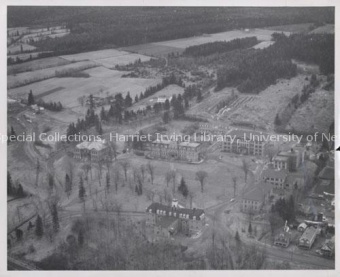

It was highly appropriate, as lumbering has always been one of the Province's most important industries, that in 1908 a course in scientific forestry was established with R.B. Miller of Yale as the first professor. Realizing the important contribution being made by the University to the economic and cult[[File:Campus1.jpg|thumb|left|340x280px | It was highly appropriate, as lumbering has always been one of the Province's most important industries, that in 1908 a course in scientific forestry was established with R.B. Miller of Yale as the first professor. Realizing the important contribution being made by the University to the economic and cult[[File:Campus1.jpg|thumb|left|340x280px]]ural life of the Province, the Legislature has from time to time increased the provincial grant. The increased expenditure was necessary if New Brunswick was to keep abreast of the times by providing its own people with the facilities demanded by progressive democratic communities elsewhere throughout the world. The ancient [[Old Arts Building|Arts Building]], now the oldest university building in Canada, was no longer adequate to the new need, especially as felt during the reconstruction period following the First World War. The [[Engineering Building]] had been erected in 1900. With the completion of the [[Memorial Hall|Memorial Building]] in 1925, the University was better able to serve the needs of an increasing number of students. The urgent necessity for expanding the work in Forestry and Geology was met by the construction of the [[Forestry and Geology Building|Forestry and Geol]][[Forestry and Geology Building|ogy Building]] in 1929 and by the establishment of separate Departments of Biology and Geology in 1930. At the same time the excellent [[Bonar Law-Bennett Library|Library Building]], designed by [[Presidents|President Jones]], met a requirement long felt keenly by all Departments. The [[Bonar Law-Bennett Library|Library]] became the repository for priceless documents relating the early history of the University; and also for the Rufus Hathaway Collection of Canadian Literature. Then in 1930, as a result of the magnificent generosity of [[Chancellors|Lord Beaverbrook]], who seventeen years later, was appointed Chancellor of the University, the [[Lady Beaverbrook Residence]] for men, designed to accommodate fifty-five students, was completed and made ready for occupation. It would be difficult to exaggerate [[Chancellors|Lord Beaverbrook]]'s generosity to the University for in addition to the Residence and the Beaverbrook Scholarships, he provided the [[Lady Beaverbrook Gymnasium]] and the [[Lady Beaverbrook Rink]], which enabled the University to offer its students excellent facilities in Physical Education. | ||

One of his greatest gifts was the [[Bonar Law-Bennett Library]], largely organized through the efforts of Dr. Alfred G. Bailey, Honorary Librarian and Dean of Arts, which helped meet the needs of the University during the period of great expansion in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the [[Bonar Law-Bennett Library]] more than doubled the capacity and added much-needed facilities, the continued growth of the University necessitated either adding a wing to the existing library, or constructing a new library on a much larger scale. The latter course was decided upon, and the University now has the [[Harriet Irving Library]], which has a book capacity of over one million volumes. Among the special rooms within the library are the Lord Beaverbrook Room, which contains many rare and valuable books from Lord Beaverbrook's personal collection. | One of his greatest gifts was the [[Bonar Law-Bennett Library]], largely organized through the efforts of Dr. Alfred G. Bailey, Honorary Librarian and Dean of Arts, which helped meet the needs of the University during the period of great expansion in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the [[Bonar Law-Bennett Library]] more than doubled the capacity and added much-needed facilities, the continued growth of the University necessitated either adding a wing to the existing library, or constructing a new library on a much larger scale. The latter course was decided upon, and the University now has the [[Harriet Irving Library]], which has a book capacity of over one million volumes. Among the special rooms within the library are the Lord Beaverbrook Room, which contains many rare and valuable books from Lord Beaverbrook's personal collection. | ||

The two decades beginning in 1956 might well be called the bricks and mortar decades. The first new building (now known as [[Toole Hall]]) was designed for the Chemistry Department. The priority given to its construction reflected the University's awakening interest in advanced[[File:Beaverbrook mackay.jpg|thumb|right|320x255px | The two decades beginning in 1956 might well be called the bricks and mortar decades. The first new building (now known as [[Toole Hall]]) was designed for the Chemistry Department. The priority given to its construction reflected the University's awakening interest in advanced[[File:Beaverbrook mackay.jpg|thumb|right|320x255px|link=Unbarchivesandspecialcollections/Forestry and Geology Building]] graduate study and research, in which that Department led the way. [[Toole Hall]] was followed by two Arts buildings ([[Carleton Hall]] and [[Tilley Hall]]), another Science building ([[Loring Bailey Hall|Bailey Hall]]), and by large additions to the [[Lady Beaverbrook Gymnasium]] and the Engineering building (now known as [[Sir Edmund Head Hall|Head Hall]]), as students enrolled year after year in ever increasing numbers. New buildings were also erected for the Faculty of Law ([[Ludlow Hall]]), for the Faculty of Nursing ([[MacLaggan Hall]]), and for the Department of Psychology ([[Keirstead Hall]]). Both the new [[Ludlow Hall|Law building]] and the additions to the [[Lady Beaverbrook Gymnasium|Gymnasium]] were gifts from the Beaverbrook Canadian Foundation, and were made possible through the generosity of [[Chancellors|Sir Max Aitken]], Chancellor of the University in succession to his father. | ||

A campus development program during the decade from 1965-75 provided the following facilities: additions to each of three earlier science buildings; two extensions to [[Tilley Hall|Sir Leonard Tilley Hall]]; a [[Central Heating Plant]]; a [[Student Union Building]]; and an addition to the Faculty of Engineering building ([[Sir Edmund Head Hall|Head Hall]]) to provide enlarged accommodations for the University's Computing Centre. The [[Aitken University Centre]], another example of the generosity of both the Canadian Beaverbrook Foundation and the Associated Alumni and Alumnae, was opened in 1976, at the end of the academic year in which Physical Education and Recreation became a separate Faculty. An [[Integrated University Complex]] behind the [[Old Arts Building]], which provides additional space for [[Physics and Administration Building|Physics]], [[Forestry Building (I.U.C.)|Forestry]], a [[Science and Forestry Library|Science Library]], and some administrative offices, was opened in 1977. | A campus development program during the decade from 1965-75 provided the following facilities: additions to each of three earlier science buildings; two extensions to [[Tilley Hall|Sir Leonard Tilley Hall]]; a [[Central Heating Plant]]; a [[Student Union Building]]; and an addition to the Faculty of Engineering building ([[Sir Edmund Head Hall|Head Hall]]) to provide enlarged accommodations for the University's Computing Centre. The [[Aitken University Centre]], another example of the generosity of both the Canadian Beaverbrook Foundation and the Associated Alumni and Alumnae, was opened in 1976, at the end of the academic year in which Physical Education and Recreation became a separate Faculty. An [[Integrated University Complex]] behind the [[Old Arts Building]], which provides additional space for [[Physics and Administration Building|Physics]], [[Forestry Building (I.U.C.)|Forestry]], a [[Science and Forestry Library|Science Library]], and some administrative offices, was opened in 1977. | ||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

Also in 1964, the [[Marshall d'Avray Hall|New Brunswick Teachers' College]] (English-speaking section) was relocated in Fredericton on the University campus, and on 1 July 1973, Teachers' College was incorporated by provincial legislation into an enlarged UNB Faculty of Education. By this move the University became heir to the intellectual tradition of the Provincial Normal School, an institution whose faculty and students had played a prominent role in shaping the provincial community. It included among its distinguished graduates [[Viscount Bennett Memorial Lectures|Viscount Bennett]], Prime Minister of Canada from 1930 to 1935. The [[Marshall d'Avray Hall|Education building]] has been named after Professor d'Avray, who came to Fredericton in 1848 to become first principal of the Normal School. | Also in 1964, the [[Marshall d'Avray Hall|New Brunswick Teachers' College]] (English-speaking section) was relocated in Fredericton on the University campus, and on 1 July 1973, Teachers' College was incorporated by provincial legislation into an enlarged UNB Faculty of Education. By this move the University became heir to the intellectual tradition of the Provincial Normal School, an institution whose faculty and students had played a prominent role in shaping the provincial community. It included among its distinguished graduates [[Viscount Bennett Memorial Lectures|Viscount Bennett]], Prime Minister of Canada from 1930 to 1935. The [[Marshall d'Avray Hall|Education building]] has been named after Professor d'Avray, who came to Fredericton in 1848 to become first principal of the Normal School. | ||

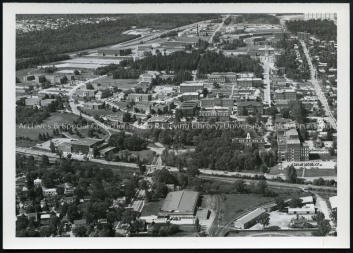

During the 1960s the University, under [[Presidents|President Mackay]]'s leadership, greatly expanded its residence facilities. The Alumnae Society had equipped and developed the [[Maggie Jean Chestnut House]] as a Women's Residence in 1949, but as the number of women students increased, it became more and more difficult to arrange for suitable accommodation in the city, and to meet this need [[Lady Dunn Hall]] was opened in January 1963 and [[Tibbits Hall|Mary K. Tibbits Hall]], named after UNB's first woman graduate, in September 1970. Meantime, residential accommodation for men was also greatly expanded by the building of seven houses and [[McConnell Hall]]. An interesting experiment in student housing was the opening of two cooperative residences, one co-educational and the other an apartment building, in 1969. Five years later these residences came under the administration of the University; one becoming a women's residence, [[McLeod House|Edith G. McLeod House]], and the other, the [[Magee House|Fred Mag]][[Magee House|ee House]], providing apartments for rental to married students and their families. [[File:Campus2.jpg|thumb|right|400x253px | During the 1960s the University, under [[Presidents|President Mackay]]'s leadership, greatly expanded its residence facilities. The Alumnae Society had equipped and developed the [[Maggie Jean Chestnut House]] as a Women's Residence in 1949, but as the number of women students increased, it became more and more difficult to arrange for suitable accommodation in the city, and to meet this need [[Lady Dunn Hall]] was opened in January 1963 and [[Tibbits Hall|Mary K. Tibbits Hall]], named after UNB's first woman graduate, in September 1970. Meantime, residential accommodation for men was also greatly expanded by the building of seven houses and [[McConnell Hall]]. An interesting experiment in student housing was the opening of two cooperative residences, one co-educational and the other an apartment building, in 1969. Five years later these residences came under the administration of the University; one becoming a women's residence, [[McLeod House|Edith G. McLeod House]], and the other, the [[Magee House|Fred Mag]][[Magee House|ee House]], providing apartments for rental to married students and their families. [[File:Campus2.jpg|thumb|right|400x253px]] The need for all these [[Alexander College|expanded facilities]] became evident in the period following the Second World War with the phenomenal increase in enrolment that took place at that time. Federal grants to veteran students, the great increase in population in the Fredericton area with the establishment of Camp Gagetown, the reputation of the University as a centre of learning under the aegis of its world-famous Chancellor, [[Chancellors|Lord Beaverb]][[Chancellors|rook]], were among the factors contributing to this end. It was symptomatic of the University's conception of the enlargement of its own scope and purpose that the Saint John Law School, which had operated in the city since 1892, became in 1923 an integral part of the University as the Faculty of Law, now situated in Fredericton. Faculties of Arts, Engineering, Forestry, and Science were set up in a reorganization of the University in 1946. The School of Graduate Studies and Research was established in 1950, followed by Faculties of Education (1969), Nursing (1973), Physical Education and Recreation (1975) and Administration (1980). | ||

The expansion of facilities for graduate studies and research provides a clear testimony to this development of the University of New Brunswick from a nineteenth-century college to a modern university. The great advocate of graduate studies in the 1950s was Dr. Frank Toole, head of the Department of Chemistry, and his policies have been carried on by his successors. Graduate study to the masters level has developed in virtually all Departments, and to the doctoral level in about a dozen, under the general administration of the School of Graduate Studies and Research. | The expansion of facilities for graduate studies and research provides a clear testimony to this development of the University of New Brunswick from a nineteenth-century college to a modern university. The great advocate of graduate studies in the 1950s was Dr. Frank Toole, head of the Department of Chemistry, and his policies have been carried on by his successors. Graduate study to the masters level has developed in virtually all Departments, and to the doctoral level in about a dozen, under the general administration of the School of Graduate Studies and Research. | ||

Revision as of 12:31, 22 May 2014

Academy of Liberal Arts and Sciences (1785 - 1800)

It is to the institutions and ideals of England's old colonial empire that one must ultimately look for the origin of the University of New Brunswick. The austere theology of the Puritans of Massachusetts was responsible for a seriousness of purpose that made thorough education an integral aspect of their peculiar culture. Uprooted from their old homes by the American Revolution, the Loyalists brought the standards of Harvard and King's College, New York, with them to the New Brunswick wilderness. It was therefore natural that when they founded the Loyalist Province in 1784, they should have made provision for the education of their young people. At that time Lois Paine, wife of Harvard graduate [William Paine], wrote that she liked New Brunswick very much, but regretted that, in the prevailing circumstances of frontier life, her children could not be properly educated.

Her plea for an academy stimulated action in the form of a memorial to the Governor-in-Council on 13 December 1785, which was signed by [Ward Chipman], [Paine], and a number of other Loyalist founders of the Province, and which represented the "necessity and expediency of an early attention to the establishment in this infant province of an academy of liberal arts and sciences." Governor Thomas Carleton immediately put it before his executive council, and on the same day the petition was presented the government passed an order-in-council as follows:

In Council 13th December 1785 Present the Governor Mr. G. Ludlow Mr. Hazen Mr. Odell Took into consideration the memorial of Dr. Wm. Paine and others praying a Charter of Incorporation to be granted for the institution of a Provincial Academy of Arts and Sciences: Also a memorial of the principal Officers of disbanded Corps and other Inhabitants of the County of York praying that part of the reserved Lands round Fredericton may be appropriated to the use of the proposed Academy.

Ordered That the Attorney and Solicitor General be directed with all convenient speed to prepare the draught of a Charter for the establishment of the said Institution.

A "draft charter," modelled on that of King's College, New York, was drawn up in 1785, and at the same timeabout 6,000 acres of land in the parish of Fredericton were reserved for the use of the Provincial Academy of Arts and Sciences. In opening the Legislature in 1792, Governor Carleton urged that increased aid be given to the "Academical Establishment," and accordingly in 1793 the Assembly voted an annual sum not to exceed £200 for that purpose. Nor was the Academy lacking "in philosophical apparatus," for in the same year Carleton asked that the astronomical instruments used in establishing the boundary between Maine and New Brunswick be presented to the seminary "as a mark of His Majesty's gracious and potential favour." There would be erected without delay a "sufficient observatory for their reception" which would enable the college "to commence a course of observations to be regularly communicated to the Astronomer Royal at Greenwich." Thus at that early date was anticipated the present Observatory building, built in 1851, which in its day housed the most up-to-date telescope in British North America.

College of New Brunswick (1800 - 1828)

Although the draft charter had been drawn up in 1785, and although the Academy was functioning shortly afterwards, at first in a cottage on what is now University Avenue, and by 1793 in its own building, the actual granting of the charter was delayed, "because of the opposition of the Bishop of Nova Scotia, who looked upon the college in Fredericton as a rival of King's College which was at the same time being established in Windsor, Nova Scotia." On 12 February 1800, the Academy was transformed into the College of New Brunswick by provincial charter. The Reverend James Bisset was the first principal. The first council of the College consisted of Chief Justice Ludlow, a former judge of the Supreme Court of New York; Jonathan Odell, the Loyalist poet of the American Revolution; Edward Winslow, an illustrious founder of the Province; and Colonel Isaac Allen of the New Jersey Volunteers. Andrew Phair, one of the early teachers, served under Benedict Arnold during the Revolutionary War. The little College, presided over after 1811 by the Reverend James Somerville, was set in a scene of pastoral beauty. In the words of a visitor in 1804, Fredericton was a pretty thing, "a village scattered on a delightful common on the richest sheep pasture I ever saw, the flocks grazing up to our door. There are altogether about a hundred and twenty houses, some very pretty, all comfortable looking, and almost everyone has a garden."

King's College (1828 - 1859)

Population and prosperity increased rapidly. By 1823 the Province had grown sufficiently in economic and social strength to warrant the expansion of the old College; and largely as the result of the vigorous policy of Sir Howard Douglas, the older institution surrendered its charter, and King's College was established by Royal Charter. Opening the College on its new site on the hill, New Year's Day, 1829, Sir Howard sounded the note that has inspired more recent generations: "Firm may this institution ever stand and flourish—firm in the liberal constitution and Royal foundation on which I have this day instituted it—enlarging and extending its material form and all its capacity to do good, to meet the increasing demands of a rising, prosperous and intellectual people; and may it soon acquire and ever maintain a high and distinguished reputation as a place Of general learning and useful knowledge."

Founded at a time

when New Brunswick was governed by the aristocratic ideals of the Family Compact, it was natural that the College should have reflected a Tory and Anglican bias. It was, Sir Howard had said, to act as a bulwark against the levelling influences of the neighbouring republic that were so abhorred by the governing class of that day. Indeed the intellectual tone of the College was for some time dominated by that point of view; and it gave rise to the bitter sectarian quarrels of the mid-century that marked one aspect of the struggle of the people of the Province for democratic self-government. The demand for religious liberty led to the abolition of religious tests in 1846. Classics, moral philosophy, logic, Hebrew, divinity and metaphysics were prominent subjects in the curriculum. Instruction became broader and increasingly "practical", as time went on, especially under the able leadership of William Brydone Jack and James Robb, who brought to New Brunswick the best scientific traditions of the great Scottish universities. While attending with great success to his professional duties, Dr. Robb did much to bring the benefits of the College to the people of the Province. He was the first scientific botanist in New Brunswick. He was the first president and the most active spirit in the Fredericton Atheneum, a society for the promotion of literary and scientific research. He commenced to write a history of the Province but died before it was completed. He founded the University Museum, and, throughout the course of his tireless life, contributed materially to the progress of agriculture and the exploration of the mineral resources of New Brunswick. His colleague, Joseph Marshall, Baron d'Avray, at one time a supporter of the Bourbon monarchy of France, founder of New Brunswick's first Normal School for the training of teachers, taught modern languages for twenty-three years, from 1848 to 1871, competently and with a courtly grace.

University of New Brunswick (1859 - Present)

New Brunswick's change in status, from a crown colony to a province enjoying internal self-government, also had an important repercussion in the field of education. Edwin Jacob, who had served as principal for thirty years, retired in 1859, and King's College was transformed into the University of New Brunswick. Henceforth education was to be on a broader democratic basis, appealing to all creeds and classes. Under the presidency of William Brydone Jack the University made rapid strides. Professor Montgomery-Campbell gave the students the benefit of his fine classical training, and Loring Woart Bailey, fresh from Harvard, took the chair of Chemistry and the Natural Sciences, bringing to the University the spirit that he had caught from his famous master, Louis Agassiz. For forty-six years, until his retirement in 1906, Dr. Bailey contributed greatly to the reputation of the University as a centre of scientific research.

Dr. Brydone Jack looked forward to the extension of the curriculum to include navigation, law, medicine, engineering and agriculture. The need for instruction in navigation belongs to that vanished era when New Brunswick was a great shipbuilding and seafaring Province; but its proposed inclusion in the curriculum was evidence of the earnest attempt to make the University serve the needs of the people. Brydone Jack's aims have long since been realized to the extent that instruction in law, forestry and engineering have for years been given at the University. But progress was slow in the years immediately following Confederation, for at that time financial aid was insufficient to carry out the ideas of the President. Nevertheless, so keen was the intellectual life of the University, along certain lines, that it achieved a reputation second only to that of the University of Toronto. It became the nucleus of a provincial culture, a fact that is attested to by the literary, scientific and political achievements of the graduates of those years—Sir George Parkin, whose fame as an a educationist was as wide as the British Commonwealth of Nations; Sir George Foster, one of the greatest of Canadian statesmen; [Bliss Carman] and [Charles G.D. Roberts], both famous poets; William Francis Ganong, distinguished scientist and historian of his native Province; and many others.

Although the movement for the emancipation of women stemmed from the intellectual revolution in Europe in the eighteenth century, the Victorians were slow to grasp the possibilities of higher education for women. Although Brydone Jack had, in his encaenial address in 1870, spoken favorably of the "higher mental training of females," it was not until 1885 that women were admitted to the University. In 1889 Miss Mary K. Tibbits graduated, the first woman student to do so. In the same year, in accordance with Brydone Jack's idea that the University should afford the training that had become necessary in an increasingly industrialized world, professors of Physics and Civil and Electrical Engineering were added to the staff during the term of office of his successor, Dr. Thomas Harrison.

The Twentieth Century

It remained, however, for the promise of the nineteenth to be fulfilled in the twentieth century. During the presidency of Dr. Cecil Charles Jones, from 1906-40, and his successors, Dr. Norman MacKenzie (1940-44), Dr. Milton F. Gregg, V.C. (1944-47), Dr. Albert W. Trueman (1948-53), Colin B. Mackay (1953-69), Dr. James O. Dineen (1970-72), and Dr. John M. Anderson (1973-79), the University forged steadily ahead.

It was highly appropriate, as lumbering has always been one of the Province's most important industries, that in 1908 a course in scientific forestry was established with R.B. Miller of Yale as the first professor. Realizing the important contribution being made by the University to the economic and cult

ural life of the Province, the Legislature has from time to time increased the provincial grant. The increased expenditure was necessary if New Brunswick was to keep abreast of the times by providing its own people with the facilities demanded by progressive democratic communities elsewhere throughout the world. The ancient Arts Building, now the oldest university building in Canada, was no longer adequate to the new need, especially as felt during the reconstruction period following the First World War. The Engineering Building had been erected in 1900. With the completion of the Memorial Building in 1925, the University was better able to serve the needs of an increasing number of students. The urgent necessity for expanding the work in Forestry and Geology was met by the construction of the Forestry and Geology Building in 1929 and by the establishment of separate Departments of Biology and Geology in 1930. At the same time the excellent Library Building, designed by President Jones, met a requirement long felt keenly by all Departments. The Library became the repository for priceless documents relating the early history of the University; and also for the Rufus Hathaway Collection of Canadian Literature. Then in 1930, as a result of the magnificent generosity of Lord Beaverbrook, who seventeen years later, was appointed Chancellor of the University, the Lady Beaverbrook Residence for men, designed to accommodate fifty-five students, was completed and made ready for occupation. It would be difficult to exaggerate Lord Beaverbrook's generosity to the University for in addition to the Residence and the Beaverbrook Scholarships, he provided the Lady Beaverbrook Gymnasium and the Lady Beaverbrook Rink, which enabled the University to offer its students excellent facilities in Physical Education.

One of his greatest gifts was the Bonar Law-Bennett Library, largely organized through the efforts of Dr. Alfred G. Bailey, Honorary Librarian and Dean of Arts, which helped meet the needs of the University during the period of great expansion in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the Bonar Law-Bennett Library more than doubled the capacity and added much-needed facilities, the continued growth of the University necessitated either adding a wing to the existing library, or constructing a new library on a much larger scale. The latter course was decided upon, and the University now has the Harriet Irving Library, which has a book capacity of over one million volumes. Among the special rooms within the library are the Lord Beaverbrook Room, which contains many rare and valuable books from Lord Beaverbrook's personal collection.

The two decades beginning in 1956 might well be called the bricks and mortar decades. The first new building (now known as Toole Hall) was designed for the Chemistry Department. The priority given to its construction reflected the University's awakening interest in advanced

graduate study and research, in which that Department led the way. Toole Hall was followed by two Arts buildings (Carleton Hall and Tilley Hall), another Science building (Bailey Hall), and by large additions to the Lady Beaverbrook Gymnasium and the Engineering building (now known as Head Hall), as students enrolled year after year in ever increasing numbers. New buildings were also erected for the Faculty of Law (Ludlow Hall), for the Faculty of Nursing (MacLaggan Hall), and for the Department of Psychology (Keirstead Hall). Both the new Law building and the additions to the Gymnasium were gifts from the Beaverbrook Canadian Foundation, and were made possible through the generosity of Sir Max Aitken, Chancellor of the University in succession to his father.

A campus development program during the decade from 1965-75 provided the following facilities: additions to each of three earlier science buildings; two extensions to Sir Leonard Tilley Hall; a Central Heating Plant; a Student Union Building; and an addition to the Faculty of Engineering building (Head Hall) to provide enlarged accommodations for the University's Computing Centre. The Aitken University Centre, another example of the generosity of both the Canadian Beaverbrook Foundation and the Associated Alumni and Alumnae, was opened in 1976, at the end of the academic year in which Physical Education and Recreation became a separate Faculty. An Integrated University Complex behind the Old Arts Building, which provides additional space for Physics, Forestry, a Science Library, and some administrative offices, was opened in 1977.

In 1964, following the recommendations of the Royal Commission on Higher Education in New Brunswick, the University of New Brunswick entered into an agreement of federation with St. Thomas University and the latter moved to the campus of the provincial University in Fredericton. At the same time, the University Of New Brunswick in Saint John opened its doors as a two-year college of arts and sciences.

Also in 1964, the New Brunswick Teachers' College (English-speaking section) was relocated in Fredericton on the University campus, and on 1 July 1973, Teachers' College was incorporated by provincial legislation into an enlarged UNB Faculty of Education. By this move the University became heir to the intellectual tradition of the Provincial Normal School, an institution whose faculty and students had played a prominent role in shaping the provincial community. It included among its distinguished graduates Viscount Bennett, Prime Minister of Canada from 1930 to 1935. The Education building has been named after Professor d'Avray, who came to Fredericton in 1848 to become first principal of the Normal School.

During the 1960s the University, under President Mackay's leadership, greatly expanded its residence facilities. The Alumnae Society had equipped and developed the Maggie Jean Chestnut House as a Women's Residence in 1949, but as the number of women students increased, it became more and more difficult to arrange for suitable accommodation in the city, and to meet this need Lady Dunn Hall was opened in January 1963 and Mary K. Tibbits Hall, named after UNB's first woman graduate, in September 1970. Meantime, residential accommodation for men was also greatly expanded by the building of seven houses and McConnell Hall. An interesting experiment in student housing was the opening of two cooperative residences, one co-educational and the other an apartment building, in 1969. Five years later these residences came under the administration of the University; one becoming a women's residence, Edith G. McLeod House, and the other, the Fred Magee House, providing apartments for rental to married students and their families.

The need for all these expanded facilities became evident in the period following the Second World War with the phenomenal increase in enrolment that took place at that time. Federal grants to veteran students, the great increase in population in the Fredericton area with the establishment of Camp Gagetown, the reputation of the University as a centre of learning under the aegis of its world-famous Chancellor, Lord Beaverbrook, were among the factors contributing to this end. It was symptomatic of the University's conception of the enlargement of its own scope and purpose that the Saint John Law School, which had operated in the city since 1892, became in 1923 an integral part of the University as the Faculty of Law, now situated in Fredericton. Faculties of Arts, Engineering, Forestry, and Science were set up in a reorganization of the University in 1946. The School of Graduate Studies and Research was established in 1950, followed by Faculties of Education (1969), Nursing (1973), Physical Education and Recreation (1975) and Administration (1980).

The expansion of facilities for graduate studies and research provides a clear testimony to this development of the University of New Brunswick from a nineteenth-century college to a modern university. The great advocate of graduate studies in the 1950s was Dr. Frank Toole, head of the Department of Chemistry, and his policies have been carried on by his successors. Graduate study to the masters level has developed in virtually all Departments, and to the doctoral level in about a dozen, under the general administration of the School of Graduate Studies and Research.

See also: Cecil C. Jones' account of UNB in Historical Foreword (1933).

Source(s):

- Adapted from Alfred G. Bailey's "Historical Sketch". UNB Calendar, 1985-86.

- Bailey, Alfred G. "Early Foundations, 1783-1829." The University of New Brunswick Memorial Volume. Ed. Alfred G. Bailey. Fredericton: University of New Brunswick, 1950.

© UNB Archives & Special Collections, 2012